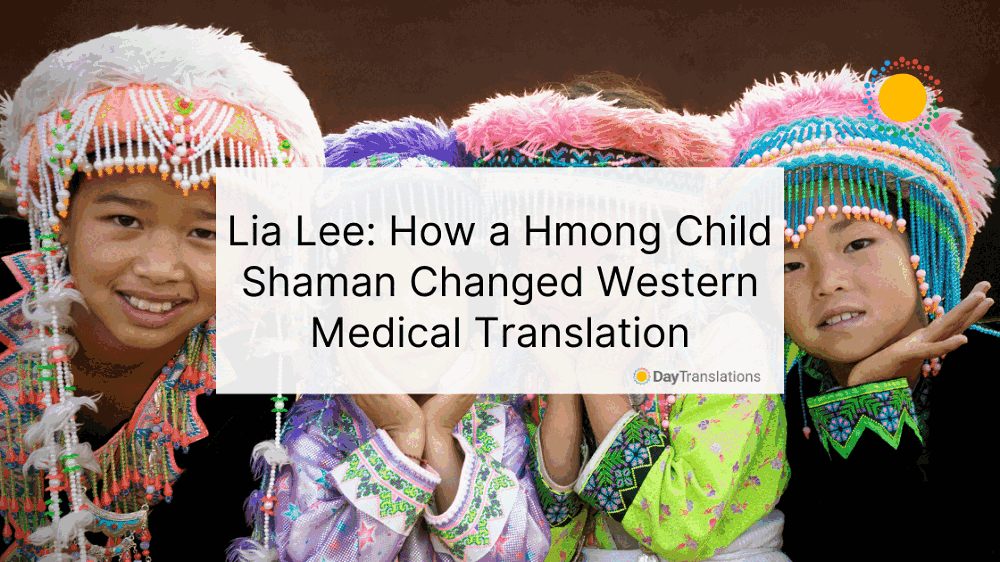

Lia Lee wasn’t supposed to live past the age of five. The perky, joyful four year old Hmong girl suffered a grand mal seizure that left her unable to speak or move.

Her doctors sent Lia’s parents out to make funeral arrangements. Nevertheless, Lia would survive. Not only that, she would change the course of western medicine and redefine the role of medical interpreters in the modern world.

Lia Lee, the daughter of a Hmong refugee family in California’s central valley, was at the fulcrum of a cultural battle. It was a battle between medical science and indigenous tradition; between western and eastern worldviews; between a handful of American doctors and a struggling immigrant family, all of them doing their best to care for a little girl.

Related Post: How Medical Interpreters Change People’s Lives

What Happens Without a Medical Interpreter?

Foua and Nao Kao Lee, Lia’s parents, couldn’t communicate with doctors at the Merced Community Medical Center. The hospital didn’t have any Hmong interpreters. Because of this, the Lees suffered misdiagnosis and errant prescriptions at the hands of Lia’s doctors.

Furthermore, the doctors didn’t understand the Lee’s perspective on what was happening to their daughter. Uninformed about Hmong customs and unsympathetic to an animistic mythos, they callously battered the family over the head with clinical orders.

Lia had her first seizure at three months old. “When the spirit catches you, you fall down,” her father said of the seizures. Such fits made Lia spiritually exceptional. She could likely have become a tvix neeb, a shaman, back in their home culture.

They wanted her to be healthy and safe; they didn’t want to damage her with an incoherent cocktail of pills. She needed “a little medicine and a little neeb,” as her father put it.

The doctors, infuriated that the Lee parents were flushing the girl’s meds down the toilet, eventually had Lia taken away from them and placed in foster care. This trauma damaged both the parents and the child, but Lia eventually returned home to her parents.

If the doctors and parents had simply had access to a Hmong interpreter, they could’ve avoided a lot of these unpleasant complications.

Born in a Conflict of Cultures

Lia’s 13 older siblings were born according to Hmong custom: at home, on the poppy farms in the mountains of Laos; quietly, with only their parents present; delivered by the mother herself into her own arms.

But the Lee family fled Laos after the American invasion, when the communists took over. They settled in the San Joaquin Valley along with a host of other Hmong refugees.

Lia was born in Merced in 1982. Unlike her siblings, Lia came into the world amidst the clamor and cold steel of an American medical facility. Her parents were denied the traditional foods that they relied on to nourish them through the birthing process. They weren’t able to discuss their options or exercise their rights because of the language barrier.

Despite this, Lia was happy and healthy, until after a few months she started having seizures. Normally, the Lees would’ve taken their sick daughter to a tvix neeb. The shaman would call her soul back to her body.

Related Post: The Plight of Refugees: How They Struggle to Integrate into a New Culture

Back From The Other World

By the time the grand mal seizure immobilized her at the age of four, Lia had been in the hospital more than a dozen times. The doctors said she would die within a year, but Lia’s mother wouldn’t have it.

She took the child home, back under her own care. When they took all of the tubes out of her, Lia cried. Her parents interpreted this as a sign that she wasn’t ready to go to the other world yet. They called in a Hmong shaman, who traveled to the upper reaches of the spirit world to bargain with Lia’s ancestors.

They asked for Lia to be allowed to remain. In exchange, they would offer the life of a sacrificial pig. Although she remained in a vegetative state for the rest of her life, to the shock of her doctors, Lia survived to the age of 30.

Nobody knows what Lia’s life would have been like if the doctors and the Lee family had been able to communicate better. Her fate may have remained the same, but it’s almost certain that the journey would’ve been less painful, confusing and frustrating for all parties involved.

A Hmong Interpreter Could’ve Helped in More Ways Than One

The Lees needed an interpreter not just to communicate the doctor’s orders to them. They needed a liaison to help bridge the chasm between Hmong tradition and western medicine.

In some ways, it was the perfect cultural storm. The doctors, armed with logic and reason, brought a typical western hubris and sense of authority.

The Hmong family, whose practices are validated by hundreds of generations of success against rugged mountain terrain and vicious political enemies, stubbornly dug their heels in and refused to comply with the doctors. It’s what their Hmong ancestors did with any authoritarian interlopers.

A good medical interpreter trains not only in language skills, but in cultural sensitivity. Because a Hmong interpreter would be sympathetic to both cultures, they could’ve helped the Lee family and the doctors work together for their common goal of helping Lia.

The Lee family’s experiences were typical of Hmong refugee experiences at American hospitals. They took place in the 1980s, before the importance of cultural sensitivity was widely acknowledged in the U.S.

Their story came into the national spotlight not only because it was such an emotionally compelling situation, but because in 1997, journalist Anne Fadiman made it the subject of her award-winning book The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures.

Lia’s Fame Lead to a Lasting Impact

Faidman’s book documented the Lee family’s struggles, and put it in context with a rich exploration of Hmong history. Faidman eschewed the typically neutral journalistic stance. She wrote with sympathy for both the doctors of her own culture and the traditions of the Hmong.

The carefully balanced narrative doesn’t offer any good guys or bad guys, just a complex situation. One of the main takeaways from the book is that both sides desperately needed to listen to the other, but were unable (or in some cases, unwilling) to do so.

By highlighting the need for greater cultural dialogue, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down had a lasting impact on the way medical professionals practice in the west. It was part of a greater dialogue about cultural understanding, that made the need for medical translation and interpretation more immediate and apparent. And it lead to lasting changes.

Universities and medical schools use Faidman’s book as part of the curriculum. Cultural competence is now a valuable quality in the truly excellent medical practitioner.

“Lia’s legacy is to give families with sick children the strength and courage to question their doctors,” says Mai Lee, Lia’s sister. “We didn’t ask those questions.”

Lia’s doctors agree. Neil Ernst, one of the Lee family’s primary physicians, said that “Lia’s a game changer. She’s altered so many people’s approaches to dealing with patients with different beliefs.”

“We saw her life ending when she was five,” added Lia’s other primary doctor Peggy Philp, “but her mother’s unconditional love taught me the value of life.”

Hmong families can now bring their own food to the hospital, even though some staff consider it fragrant or smelly, depending on their opinion of the Hmong people. California hospitals now even permit Hmong shamans to practice alongside medical doctors.

Related Post: 5 Reasons Why Medical Translation May Be For You

Medical Translators and Interpreters Since Lia Lee

The need for qualified medical translators and interpreters has never been higher. Or perhaps it has just never been more widely acknowledged. Since the time of Lia’s first hospitalizations, America has seen an overhaul of its medical practices. Any serious medical treatment facility now considers translators and interpreters to be essential.

The American Healthcare Act expanded the requirements for hospitals to make medical interpreters available. Any hospital that receives federal funding must provide at least some kind of translation or interpretation services, by law. However, there are not always enough medical translators and interpreters to keep up with the public’s needs. Check our free guide on healthcare language services for more on this matter.

Recently, immigration and refugees have taken center stage in America’s politics again. Now more than ever, we need professionally trained medical translators and interpreters from all cultural backgrounds to lead the way. The path they open is one to greater health, but also to a richer cultural understanding.

Any time a western medical practitioner parleys successfully with a family from another culture, we can remember Lia Lee. And when the learning goes both ways, we can thank her family, whose struggles advanced the public conversation around interpretation and cultural understanding.

Inn Lunar

Posted at 17:42h, 11 Novemberovercome your seeing. look onto wall not onto side which you cant see – you look where you can only use imagination not grab some real effective matter

朱真明

Posted at 03:50h, 19 JanuaryYou should be aware that the term Western Medicine used in this day and age is inappropriate. The appropriate term is Biomedicine. Clearly reflecting that this type of medicine is based of Biology(or at least a narrow interpretation of it). To continue to use “Western” is to undermine all of the ways in which non-western countries have added to and benefited Biomedicine and instead focus on some vague geographical location that is known as the West.